Published December 2, 2024, updated January 23, 2025

If you're a Python developer, you may have heard murmurings about this new tool called uv that everyone's talking about.

And if you're like me—generally wary of the latest tooling fad—you might be inclined to dismiss it as another hype craze that will be here and gone faster than you can say "pipenv".

This post is about why I think that's wrong, why uv feels like the future of Python package and project management, and how you can start using it in your projects today.

If you've been hearing about uv and were looking to learn more or try it out, this is the post for you!

Intended audience

This post is for anyone interested in learning more about uv and how to use it in their Python projects.

I come from a Django background and so will focus on the uv workflows relevant to Django projects:

- Setting up Python environments.

- Installing and managing packages.

- Building and running your apps.

Uv also does a lot on the packaging side of things—i.e. helping you build and publish your own Python packages. This post mostly glosses over those use cases, as they aren't relevant to most projects that use Python.

This post should be suitable for beginners—I don't assume much knowledge of Python or other tools. But if you aren't a developer using Python you probably won't benefit much from this. In fact, if that's you—why are you even reading this? Go outside, touch some grass and appreciate that you've never had to think about Python packaging!

Ok—convinced you want to continue?

Let's get into it!

What is uv?

Let's start with the basics. What actually is uv?

One of the things that makes uv hard to explain is that it is not just one thing. This line describing uv from its homepage helps set the stage:

🚀 A single tool to replace pip, pip-tools, pipx, poetry, pyenv, twine, virtualenv, and more.

That's a lot of tools!

The site then goes on to list about 10 other things uv can do, but let's ignore those for now.

The simplest way to think of uv is this: However you've been managing your Python environments and dependencies, uv does that for you, but better and faster.

Seriously! No matter what you're using and how you're using it—unless you are doing something pretty unusual—uv can probably handle it. It will also probably handle it better, and almost certainly faster. In most cases, way faster.

Why use uv?

You might be thinking—I already have a workflow I'm happy with using virtualenv/pip/pip-tools/poetry/etc. Why should I bother with this new thing?

Here I'll offer three reasons:

- Uv is insanely fast.

- Uv does everything you need.

- Uv's future is bright.

I'll dig into each of these a bit below, though if you're already convinced you want to try out uv feel free to skip ahead.

Uv is insanely fast

This will be a recurring theme for the entire post—but I'll just emphasize it here. Uv is insanely fast.

It is not an exaggeration to say that most of the things I now use uv for are about 20 times faster than before I switched. 20 times!

This means things that felt slow (e.g. 20 seconds) now feel fast (1 second). And things that felt pretty fast (e.g. 2 seconds) now feel instant (.1 second). I wasn't complaining about speed before adopting uv—but now that I'm using uv it all just feels like magic.

Uv does everything you need

I think uv's motto should be something like: Come for the speed. Stay for the versatility.

While speed is definitely the most compelling reason to switch to uv, the fact that it's a single tool that does everything you need to do with Python is just... really nice. As uv points out in the blurb above, you can basically stop using all other tools and go all-in on uv. This simplifies and centralizes a lot of things in the ecosystem.

Uv's future is bright

One of the most controversial aspects of uv is the fact that it is created and owned by a venture-backed company (Astral—which is also behind the linting tool, ruff).

What this means in the short term is:

- Uv has a ton of resources behind it.

- Uv wants everyone to adopt it.

These are good things! And the way that they have played out so far is that a bunch of very smart people have worked really hard to make uv, the documentation, and the entire ecosystem awesome. The team is constantly shipping updates, responding to Github issues, and generally just pouring tons of effort and resources into uv.

And the results have been obvious—with uv going from something that didn't do all that much, to today being capable of taking over your entire project.

Now, it's definitely worth noting that at some point the VCs behind the scenes will be coming along to collect their paychecks. So it's not guaranteed that uv's future will always be bright. But for the time being, the sheer rate of improvement makes the trajectory of uv look great.

How worried should we be about uv lock-in?

Lock-in is probably the biggest legitimate concern to have about uv. While the tool is fantastic and the team behind it seems great—history is littered with examples where the need to make money has turned a good and open ecosystem into one designed to turn a profit. Should we be worried about a future world in which Astral locks us into their world and then milks us for cash?

I think it would be naive not to worry about that at least a little. But also, the fact that uv is permissively licensed (under MIT) means that if the team does decide to become evil, the community has an escape hatch to take over.

My personal feeling is that it's reasonable to be worried about these things happening, but it shouldn't stop you from using uv today. And hopefully Astral will find a way to make money that allows uv to be open and awesome forever.

Ok, so that's the why. Now let's get into the what.

Installing uv

Before we get into working with uv, we just have to quickly cover how to get up and running.

Uv is a single command line executable. There are a number of ways to install it, but the easiest is to use the provided installation script:

curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

After you run this, you'll have a new command-line utility that you run anywhere just by typing "uv":

$ uv

An extremely fast Python package manager.

Usage: uv [OPTIONS] <COMMAND>

So what can you do with this thing?

Here's a run down on some common tasks it handles for you.

Adopting uv into your existing workflows

There are two different ways of using uv. The first is to just plug it in as a replacement for something you're already doing. This is the most accessible way to adopt uv, and is a good way to get the speed benefits of uv without having to change much else about your workflows.

Later on we'll see how to use uv to work in a new way, but for now let's just cover some of the common things you're likely already doing.

Installing Python with uv

You don't have to use uv to install Python—it will happily find and work with the Python installations you have already. But if you want to use it to install Python you can, by running:

uv python install 3.12

I find this is easier and more reliable than manually installing Python through a more standard channel. No fiddling with apt repositories or downloading installers. Just "uv python install" and you're off to the races!

Incidentally—in researching this post, I learned that managing Python installations is also the primary job of pyenv,

so we've already eliminated one of those tools from uv's description!

Let's update it so we can keep track:

🚀 A single tool to replace pip, pip-tools, pipx, poetry,

pyenv, twine, virtualenv, and more.

More reading: uv's Python docs.

Managing virtual environments with uv

When I first started using Python—almost 20 years ago at this point—I didn't even know what a virtual environment was; I just shoved all my libraries into system Python. This worked out fine until I started working on more than one project and ran into all kinds of issues with version conflicts. And so I discovered the benefits of virtual environments—sandboxed Python installations you can use for a single project.

Python environment tooling has come a long way since those days.

First we got virtualenv—a third party tool that let you create separate environments for each project.

Then, with Python 3.3 we got venv—basically virtualenv, but built into Python.

Now, the idea of running Python without some kind of virtual environment feels like sacrilege to me.

Ok, what does this have to do with uv?

Well, uv provides a drop-in replacement to those existing tools. So now, instead of creating a virtual environment by running something like:

python3.12 -m venv /path/to/environment

You can use uv instead:

uv venv /path/to/environment --python 3.12

One nice thing about this is that you don't have to worry about Python installs anymore!

If uv can't find the right Python version, it will just go ahead and download and install it for you.

This also means you don't ever really need to use that uv python stuff I just mentioned above,

but it's there if you need it.

Returning again to our uv description, we've now also eliminated virtualenv with a simpler replacement:

🚀 A single tool to replace pip, pip-tools, pipx, poetry,

pyenv, twine,virtualenv, and more.

More reading: uv's environment docs.

Aside: Where should I put my virtual environment?

TL;DR: in a ".venv" folder local to your project.

For a long time there wasn't a clear best-practice on exactly where to put your virtual environments,

with the two competing options being some centralized place on your machine like ~/.virtualenvs or

~/environments or using a local-to-the-project folder like venv or .venv or env.

These days, for the most part, the local-to-the-project option won out (thanks node_modules!) and that's the most common place you'll see Python environments these days. Among other benefits, this makes it easier for IDEs to find your environment.

Later in this post we'll talk about how you can go "all-in" with uv's environment management

and ditch the venv and pip calls entirely.

If you do this, uv will put your environment in a local-to-the-project folder called .venv---so

that's what is recommended here.

Packages with uv using the pip interface

Uv for environments is a nice convenience, but here's where things start to get good.

So, in addition to using uv for environments, you can also use it to manage packages. Once again, uv provides a very familiar interface for this out-of-the-box.

Basically, instead of running:

pip install django

You instead run:

uv pip install django

So why is this better?

In a word, speed.

Using uv to manage your Python packages is (seriously!) 10-20x faster than using regular pip. When I run it, it's so fast that I often worry it didn't work (it did).

If you take nothing else away from this post, just start using "uv pip" instead of "pip" and your life will already be substantially better.

Back to our description—we've now also replaced pip with something way better:

🚀 A single tool to replace

pip, pip-tools, pipx, poetry,pyenv, twine,virtualenv, and more.

More reading: uv's packages docs.

Uv for managing project dependencies

Ok, so we've seen how we can use uv to set up our Python environment and install packages. Now let's start getting into the more interesting stuff.

The next common need most projects have is a way to manage their dependencies—i.e. the set of Python packages

that the project... well... depends on.

This is where you would say something like "this Python project depends on the django and requests packages".

Python dependencies have historically been included in things like requirements.txt, setup.py, and pyproject.toml files,

and managed by a variety of tools like pip-tools,

Poetry, PDM,

Pipenv, and Conda.

In addition to sometimes helping with environments, what most of these tools do is help take a set of base requirements—packages your project uses directly—and turning it into a set of complete requirements—packages those other packages need to run. They also help with keeping packages pinned to specific versions and resolving dependencies between your packages.

Why do we need these tools at all?

Let's explain why this is necessary with a simple example.

Let's say you want to use Django in a new project,

so you run pip install django.

This will output something like the following:

$ pip install django Collecting django Using cached Django-5.1.3-py3-none-any.whl.metadata (4.2 kB) Collecting asgiref<4,>=3.8.1 (from django) Using cached asgiref-3.8.1-py3-none-any.whl.metadata (9.3 kB) Collecting sqlparse>=0.3.1 (from django) Using cached sqlparse-0.5.2-py3-none-any.whl.metadata (3.9 kB) Using cached Django-5.1.3-py3-none-any.whl (8.3 MB) Using cached asgiref-3.8.1-py3-none-any.whl (23 kB) Using cached sqlparse-0.5.2-py3-none-any.whl (44 kB) Installing collected packages: sqlparse, asgiref, django Successfully installed asgiref-3.8.1 django-5.1.3 sqlparse-0.5.2

What this actually did was install three packages, django, asgiref, and sqlparse. This is because django needs those other two packages to work. We've also gotten specific versions of these packages (django-5.1.3 , asgiref-3.8.1, and sqlparse-0.5.2).

These tools essentially help you say "I only care about Django", while also ensuring that you get the right, consistent versions of everything else you need behind the scenes.

This is a simple case, but things get much more complicated when you have packages that depend on other packages that depend on other packages with different version constraints, and so on.

I come from the school of pip-tools—which has a very simple way of handling this problem.

You keep your base requirements in a requirements.in file that looks something like this:

django>=5.0

Then you run a command like this to generate your requirements.txt file:

pip-compile requirements.in -o requirements.txt

After you do this, you'll have a requirements.txt file that looks like this:

# This file is autogenerated by pip-compile with Python 3.11

# by the following command:

#

# pip-compile requirements.in

#

asgiref==3.8.1

# via django

django==5.1.3

# via -r tmpreqs.in

sqlparse==0.5.2

# via django

Now our requirements.txt file gets the complete set of dependencies, and can be used with (uv) pip install to

install all our exact dependencies with pinned versions.

But, we can manage our base dependencies by adding/removing/upgrading things in the requirements.in file

and re-running the command.

This works great, and I thought that I'd never find something I liked better—but again, uv cheated! Just like with venv and pip, uv made itself a pip-tools replacement.

So, if you love pip-tools and don't want to change your workflow, all you have to do is install uv and then instead of writing the above command you write:

uv pip compile requirements.in -o requirements.txt

And once again, the killer feature is speed.

uv pip compile runs (literally!) about 20 times faster than pip-compile.

I just ran them side-by-side on the Django project that hosts this site and

pip-compile took 18 seconds. Uv took less than a second.

We've now eliminated pip-tools with a better, faster replacement:

🚀 A single tool to replace

pip,pip-tools, pipx, poetry,pyenv, twine,virtualenv, and more.

Again we could stop there, but there's still much more to uv, so let's keep going!

More reading: uv's "locking environments" docs.

Aside: How is uv so fast?

One of the consistent things you will notice about uv is that it is blazing fast. How do they do it?

I'm by no means an expert on this topic, but the high-level answer is two main things:

- It's written in Rust, which is just super-fast.

- The team has put a lot of hard work into lots of tricks to optimize every step of the process.

If you're interested in learning more about uv's internals and how they make it so fast, I highly recommend this conference talk from Charlie Marsh, the founder of Astral (the company behind uv).

Cheatsheet: uv versus existing tooling

Ok we've now covered how to use uv as a drop-in replacement for most of the Python tooling you're already using. Here's a quick summary:

| What | Previous Tools | Command (example) | With uv |

|---|---|---|---|

| Installing Python | homebrew, apt, deadsnakes, pyenv, etc. | sudo apt install python3 |

uv python install |

| Creating virtual environments | venv, virtualenv | python -m venv .venv |

uv venv |

| Installing packages | pip | pip install django |

uv pip install django |

| Building dependencies | pip-tools, poetry | pip-compile requirements.in -o requirements.txt |

uv pip compile requirements.in -o requirements.txt |

Adopting uv as a new workflow

Up till now we've been talking about how to use uv as a drop-in replacement for specific tools that you're probably already using. And the fact that you can harness the power and speed of uv without changing much else about your workflow is very much by design! The team behind uv knows that adopting new tools takes time, and the easiest way to get people to do it is to offer easy-to-adopt solutions.

That said, uv has its own vision of being the one-tool-to-rule-them-all. And if you're brave enough to adopt it, you can update ~all your workflows—mostly for the better!

What do I mean?

Well everything I described above is what I would call the old way of doing things. But uv also has a set of new APIs which streamline much of this stuff for you.

This section will discuss how that works.

Prerequisite: the files uv uses

Before you can go all-in with uv, you have to update your current packaging files to the format it expects.

Since I come from the pip-tools world, I'll describe those files in terms from that ecosystem, but the concepts will be similar to those found in poetry and various other tools.

Uv uses two main files to understand your project's environment:

- The

pyproject.tomlfile - The

uv.lockfile

We'll cover these one at a time.

The pyproject.toml file

The pyproject.toml file is a standard file used for Python Packaging

and other tooling like linters, type-checkers, etc.

Uv uses this file and its standard markup to find out information about your project and its dependencies.

Your project might already be using this file even if you've never used uv.

From a purely package-management perspective, you can think of the pyproject.toml file as your

requirements.in file from pip-tools

(it has other stuff in it for other workflows but we won't worry about that now).

In other words—it defines the primary project dependencies, but not necessarily the exact versions,

or the dependencies of the dependencies, and so on.

It also includes some information about the project itself, what versions of Python it supports, etc. Here's a typical example:

[project]

name = "uv-demo"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Add your description here"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.12"

dependencies = [

"django>=5.0",

]

The uv.lock file

If pyproject.toml is your new requirements.in file, then uv.lock is your new requirements.txt file—it will

keep track of all your project's dependencies, dependencies of your dependencies, and so on.

Just like requirements.txt, if you're using uv you would never edit the uv.lock file by hand,

but would instead keep it up to date using the uv command line application.

For that reason—and the fact that it's relatively ugly-looking—we won't bother showing it here,

but you can view the lockfile used by the above pyproject.toml file here.

With that covered, let's show how we can use uv's own workflow to replicate what we outlined above!

Further reading: uv's project structure documentation.

Why are uv.lock files so complicated looking?

One of the aspects of the uv.lock file that can be jarring to people used to requirements.txt is just how much stuff is in it. These files are way more complicated than a simple requirements.txt file!

The short answer to why uv.lock is more complicated is that it's doing a lot more work. Uv's lock files are cross-platform, which means that in addition to pinning packages to specific versions, they also pin specific versions to specific environments.

For example, if you look closely at the generated lockfile

you'll see it also includes a library called tz-data that didn't show up in our requirements.txt file at all.

This is because django only needs tz-data if you're running on a Windows 32-bit architecture!

But if you use uv on that environment you'll get tz-data installed too!

Basically, the uv.lock file keeps enough information to replicate a consistent install on any supported Python version, operating system, etc.

This isn't the only thing making the uv.lock format more complicated—it also stores more information about exactly where and how to get the packages—but it is the most useful reason.

Setting projects up to use uv

Alright, enough with the theory. Let's finally get into how we can actually use this thing!

If you're starting a new project, run:

uv init myproject

Which will create a new directory with a few files, including a pyproject.toml that looks like the one above.

Alternatively, if you're porting an existing project already you can just copy/paste

something like the above into a new file called pyproject.toml and you should be good to go!

Working with environments

Way back above we mentioned that uv's tooling will create a .venv folder in your project

for your Python environment.

To do that in a native-to-uv way you can run:

uv sync

This command will:

- Find or download an appropriate Python version to use.

- Create and set up your environment in the

.venvfolder. - Build your complete dependency list and write to your

uv.lockfile. - Sync your project dependencies into your virtual environment.

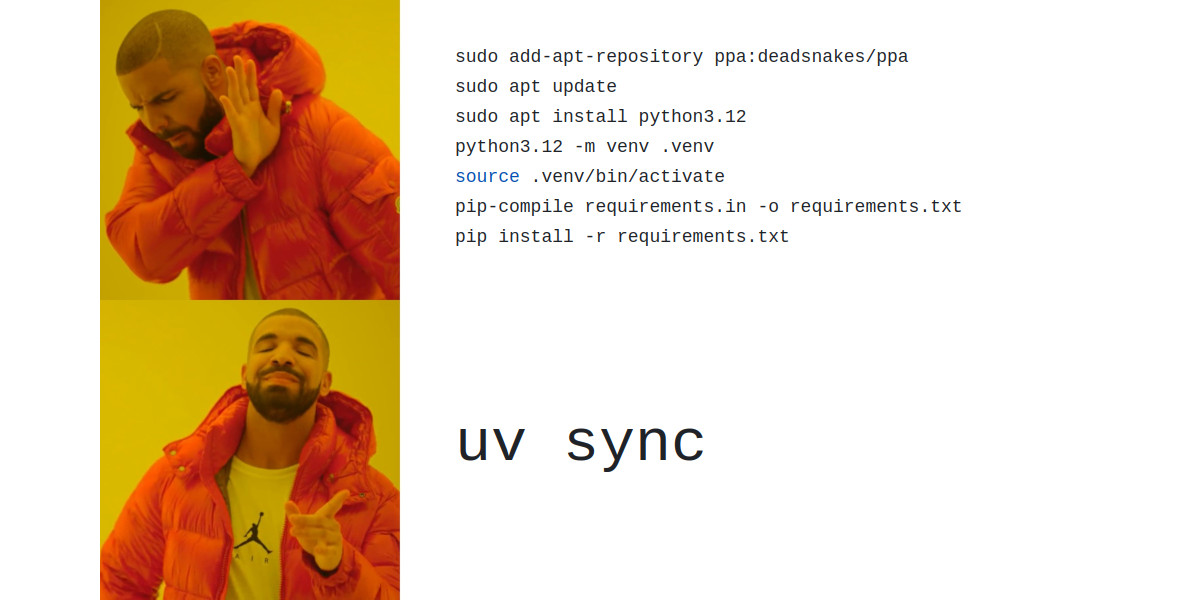

In a single command (that is also blazing fast, btw) we've essentially done all of this:

sudo add-apt-repository ppa:deadsnakes/ppa

sudo apt update

sudo apt install python3.12

python3.12 -m venv .venv

source .venv/bin/activate

pip-compile requirements.in -o requirements.txt

pip install -r requirements.txt

python manage.py runserver

We've now saved ourselves a lot of keystrokes and a lot of time!

More reading: uv's project docs.

Running Python

Now we've got our environment. In the old world, the next logical thing to do would be to activate it, which we can do like this:

source .venv/bin/activate

After running this, future python commands will run in the environment and we can do everything we're used to! I use this workflow regularly, and it's great if you don't want to update your muscle-memory.

But we're not in the old world anymore.

One of the amazing consequences of just how fast uv is, is that uv sync—especially with a hot cache—is

is basically instant.

This means we can sync our environment every time we run a python command!

Uv has a built-in command for this called uv run.

So, in a Django world, instead of running:

uv sync

source .venv/bin/activate

python manage.py runserver

You can just run:

uv run manage.py runserver

This will:

- Sync your environment (basically instant)

- Run

python manage.py runserverin the updated environment

Practically, what that means is you can just replace every time you type "python" with "uv run" and you never have to worry about syncing or managing your environment at all! Uv will just check if everything's up to date, fix any issues, and then run your command. And—of course—this all happens so fast you don't notice it.

More reading: uv's docs on running commands.

🚀 Get a head start on your next Python SaaS.

If you're a Python developer, you might want to consider SaaS Pegasus for your next project. It's a Django-based starter project with account management, billing, teams, a modern front end, and near-instant deployment built in. And of course, it fully supports uv out-of-the-box.

Working with dependencies

Ok, so we know how to set up our environment and run commands inside it. But how do we manage our dependencies?

There are a number of ways to handle this, but the simplest one is using uv add and uv remove.

# install a package

uv add requests

# remove a package

uv remove requests

These commands are basically a one-stop-shop that will:

- Update the dependencies in your pyproject.toml file.

- Update the uv.lock file.

- Sync your environment.

Alternatively, you can edit your pyproject.toml file directly and run uv lock (to update just the lock file)

or uv sync (to update the lock file and the environment).

Congratulations, you can now manage your environment entirely in uv!

More reading: uv's dependencies docs.

Cheatsheet: Common operations in uv's workflows

We've officially gone all-in with uv! Here's a quick cheatsheet for how you can do common operations in this new world:

| What | Uv's version | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Project dependency file | pyproject.toml |

Base / core dependencies are defined in this file. |

| Project lock file | uv.lock |

Derived dependencies are managed in this universal lockfile. |

| Installing Python | uv sync or uv run |

Uv will find or install Python if needed as part of syncing or running code in your environment. |

| Creating virtual environments | uv sync or uv run |

Uv will create a virtual environment if needed the first time you use it. |

| Installing packages | uv sync or uv run |

Uv installs all packages it needs into your environment every time you use it. |

| Building dependencies | uv sync or uv run |

Uv rebuilds the lockfile from dependencies every time you run it. |

| Add a package | uv add |

Will add the package to pyproject.toml, uv.lock, and sync your environment. |

| Remove a package | uv remove |

Will remove the package from pyproject.toml, uv.lock, and sync your environment. |

| Upgrade a package | uv sync --upgrade-package <package> |

Will upgrade the package in your uv.lock file and sync your environment. |

| Upgrade all packages | uv lock --upgrade |

Will upgrade all packages in your uv.lock file (according to the version constraints in pyproject.toml). |

Advanced usage

Alright, those are all the basics, and most of what you need to switch your projects to uv. The rest of this post covers other things I ran into while adding uv support to my Django starter project, SaaS Pegasus.

It is by no means a comprehensive set of topics surrounding uv, just the ones that I've run into so far.

I'll keep this section shorter and more concise and focus on just getting the key information across.

Working with dev and production requirements

It's quite common to break your requirements up into regular, development and production requirements. In the pip-tools world this often means having different requirements.in files for each set.

In uv and pyproject.toml support dependency groups which are designed for this use case.

Adding, removing, and changing packages in different dependency groups

You can add a package to a dependency group by passing the --group flag to uv add:

uv add --group production gunicorn

This will add the package like this in the pyproject.toml file:

[project]

name = "uv-demo"

version = "0.1.0"

description = "Add your description here"

readme = "README.md"

requires-python = ">=3.12"

dependencies = [

"django>=5.0",

]

[dependency-groups]

production = [

"gunicorn>=23.0.0",

]

uv add also supports a --dev flag which automatically adds dependencies to a dev group:

uv add --dev django-debug-toolbar

# this command does the same thing

# uv add --group dev django-debug-toolbar

That will update the file like this:

[project]

name = "uv-demo"

# other project contents here

[dependency-groups]

production = [

"gunicorn>=23.0.0",

]

dev = [

"django-debug-toolbar>=4.4.6",

]

Installing packages in different dependency groups

By default, uv will install all packages in the main group and dev group when you run things

like uv sync and uv run.

If you want to include or exclude packages you can pass them using --group, --no-group, and --only-group flags.

For example, to install just the base + production dependencies, you'd run:

uv sync --no-group dev --group prod

It's annoying to have to specify groups inclusion/exclusion every time you run uv sync and uv run,

which is probably why uv defaults to including all dev dependencies!

*More reading: uv's development dependencies docs

Disposable environments and tools

One of the cool things about uv being so darn fast is that you can very quickly:

- Set up a virtual environment

- Install packages into it

- Run a command in that environment

This makes it very easy run things on the Python CLI without having to install anything. Uv can just build a quick little disposable environment for you and get rid of it after you're done. Uv provides a "tools" workflow for these situations.

For example, you can make an ascii cow say something like this:

$ uv tool run pycowsay hello from uv

-------------

< hello from uv >

-------------

\ ^__^

\ (oo)\_______

(__)\ )\/\

||----w |

|| ||

Or create a new Django project like this:

uv tool run --from django django-admin startproject myproject

There is also a uvx command that is equivalent to uv tool run.

uvx pycowsay hello from uv

Incidentally, this replaces pipx, so we've finally eliminated another item from our description:

🚀 A single tool to replace

pip,pip-tools,pipx, poetry,pyenv, twine,virtualenv, and more.

More reading: uv's tools docs.

Uv and Docker

When I migrated my production applications to uv I had some trouble with my production Dockerfiles.

At first I tried to update all my Python commands to use things like uv run gunicorn instead of gunicorn

but I kept running into issues with that approach (sorry, I don't remember exactly what they were and I should have

documented it better).

Anyway, what I eventually figured out, is that I didn't have to go through that trouble! Yes, I still had to update my Dockerfile to build the environment with uv, which I did like this:

# Stage 1: Build the python dependencies

FROM python:3.11-slim-bookworm as build-python

# This approximately follows this guide: https://hynek.me/articles/docker-uv/

# Which creates a standalone environment with the dependencies.

# - Silence uv complaining about not being able to use hard links,

# - tell uv to byte-compile packages for faster application startups,

# - prevent uv from accidentally downloading isolated Python builds,

# - pick a Python (use `/usr/bin/python3.12` on uv 0.5.0 and later),

# - and finally declare `/app` as the target for `uv sync`.

ENV UV_LINK_MODE=copy \

UV_COMPILE_BYTECODE=1 \

UV_PYTHON_DOWNLOADS=never \

UV_PROJECT_ENVIRONMENT=/code/.venv

COPY --from=ghcr.io/astral-sh/uv:0.5.2 /uv /uvx /bin/

# Since there's no point in shipping lock files, we move them

# into a directory that is NOT copied into the runtime image.

# The trailing slash makes COPY create `/_lock/` automagically.

COPY pyproject.toml uv.lock /_lock/

# Synchronize dependencies.

# This layer is cached until uv.lock or pyproject.toml change.

RUN --mount=type=cache,target=/root/.cache \

cd /_lock && \

uv sync \

--frozen \

--no-group dev \

--group prod

This basically installs uv, sets some production optimizations, and then runs uv sync on the production requirements.

One key thing to note is it uses UV_PROJECT_ENVIRONMENT=/code/.venv to tell uv exactly where to create the environment,

since we need it in the next step.

I chose to put my environment in the "normal" .venv folder, but you can put it anywhere.

After building our environment, in a later stage of the Dockerfile we just copy that entire environment across and make sure it becomes the default one to use by putting it on the path:

WORKDIR /code

COPY --from=build-python --chown=django:django /code /code

# make sure we use the virtualenv python/gunicorn/celery by default

ENV PATH="/code/.venv/bin:$PATH"

Now python, gunicorn, celery, and friends pick up the right environment because they are listed

first in the path.

This ended up being way easier than fiddling with uv run.

Big thanks to Hynek Schlawack and specifically this post for helping me figure this out!

Building and publishing projects

Finally, I will just mention that uv can also build and publish your packages to PyPi. I won't get into the details of this, but with it we have finally replaced twine, which helps you do this. And publishing is the last major feature of poetry that we hadn't already covered, so we can eliminate that too.

🚀 A single tool to replace

pip,pip-tools,pipx,poetry,pyenv,twine,virtualenv, and more.

More reading: uv's publishing docs

Conclusion and resources

Well, this got a lot longer than I intended, but hopefully it was useful!

As you probably gathered, I'm very bullish on uv and am already adopting it in all my projects. I hope this inspires you to try it out and do the same!

I wanted to give a shout out to the following resources, which—in addition to the excellent documentation—helped me better understand how to make the most of uv:

- I already mentioned this above, but Charlie Marsh's talk on uv is a useful overview of both what uv can do and how it works.

- Simon Willison's blog has a number of practical posts about using uv

- Hynek Schlawack has a great video overview of uv, as well as a good write up on using uv with Docker.

- Anže Pečar's blog on uv and Django.

Thanks for reading!

While you're here, you may want to check out my Python SaaS Boilerplate, SaaS Pegasus. Pegasus has been used to start thousands of Django projects, and can help save you weeks of development time on your next web project.